Harold Larwood was one of England’s finest fast bowlers — and he was from a small mining town in Nottinghamshire

We explore the career and the legacy of the cricketing legend...

Our county is known for plenty of famous faces, and one of the most significant sportspeople it has produced is cricketer Harold Larwood.

In commemoration of the 30th anniversary of his passing on July 22 2025, we’ve delved into his origins, his controversial Bodyline incident, and the legacy that he left that still stands in Nottingham today. For this, we spoke to Trent Bridge heritage volunteer Peter Smith.

If one of your favourite things to do in Nottingham is learning about the area’s historical figures, Larwood was one of the finest sportsmen our county has produced. For more features and local guides, subscribe to receive our articles in your inbox for free.

Bodylines, statues, and clocks — the legacy of Harold Larwood

By Sam Swain

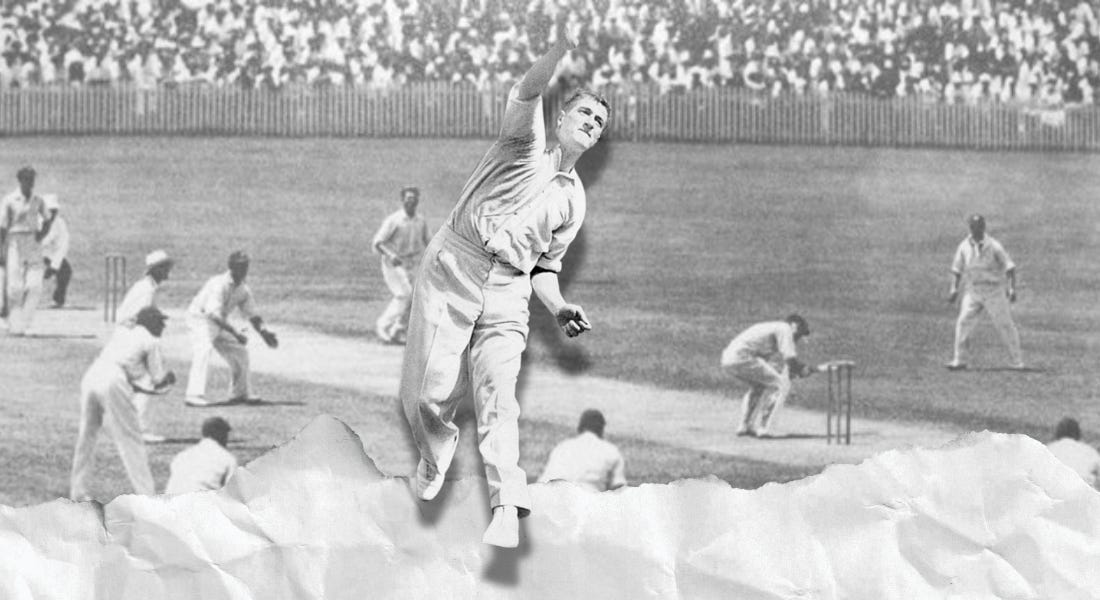

Kirkby-in-Ashfield isn’t known as a cricketing town. It’s a market town and former lynchpin of Nottinghamshire’s coal mining history, thanks to the access the old Midland Rail network provided. Soot-blackened clothes were the uniform, not the pristine cricket whites of England’s finest cricketers — but it was often said if England needed a fast bowler, they’d just whistle down the pits of Nottingham and Yorkshire. Out of the dust came one England’s fastest, most feared bowlers in test match history.

A statue of Harold Larwood stands proudly in the centre of Kirkby where the old precinct was, now overlooked by a supermarket and a discount store. It’s been in Kirkby since 2002 and its current spot since 2015, where statues of fellow Kirkby lad Bill Voce and one of the finest players of all time, Australian Don Bradman were added.

The statues are not just a tribute. They tell the story of one of Test Cricket’s most notorious episodes — of a sporting series so intense that it threatened the diplomatic relations of two commonwealth countries. The statues tell the story of the Bodyline Ashes series of 1932-33.

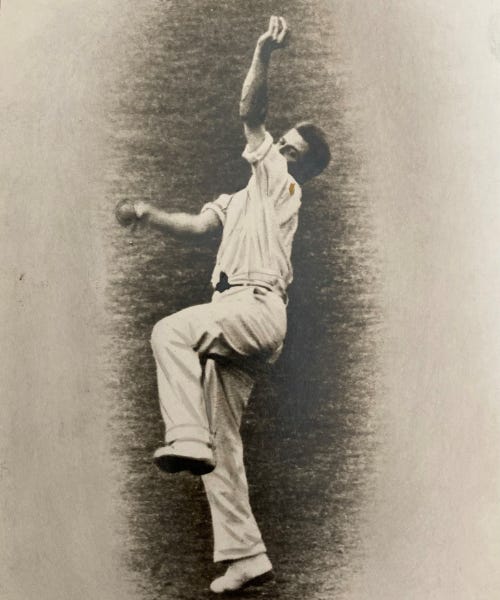

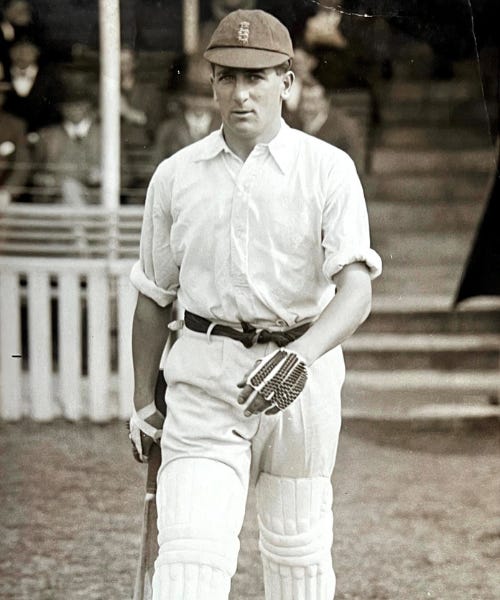

Harold Larwood would have probably spent a lifetime down the pit were it not for cricket — although somewhat ironically, it was his time in and around the colliery that led to his fearsome bowling ability. “Despite being slightly built and not a tall man (Larwood stood at 5 foot 8 inches), he had great strength in his arms and shoulders and was the fastest bowler of his era,” says Peter Smith, Trent Bridge heritage volunteer. This would have come from spending formative years in charge of pit ponies.

Men like Larwood were suited to the relative brutality of fast bowling in the early 20th century. The well-to-do would stand and bat, while the working-class men would do the hard yards bowling at them. It wasn’t a glamorous or well-paid position compared to today (Australian captain Pat Cummins took home £2.8m for two months in the Indian Premier League in 2025), but for Harold Larwood, fast bowling was an escape from a life in the mines.

Larwood signed for Nottinghamshire in 1924 and, under the stewardship of Arthur Carr, set the standard for fast bowling in the County Championship. “There were no speed guns at the time, but he is estimated to have reached 90mph, which would match the quick bowlers of the modern era,” says Peter. For context, with modern pitches, equipment and conditioning, 90mph is still the benchmark today.

Peter continues, “It was the combination of high-speed bowling with accuracy of line and length that made Larwood such a threat to opposition batters. It was this that made him the best, almost the only, hope of wresting The Ashes back from a dominant Australian side, spearheaded by the scoring phenomenon that was Donald Bradman.”

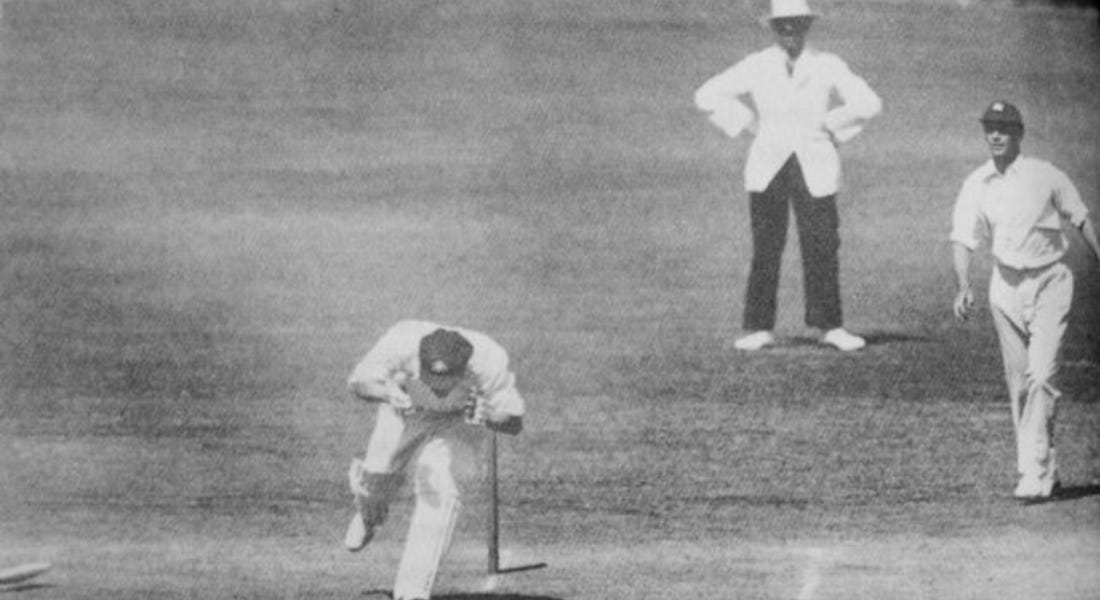

For many, Don Bradman remains the benchmark of batting. He maintained a career average score in Tests of 99.94, notching just under 7,000 test runs among countless other records. He was the talisman of an Australian side, and he was deemed worthy of special treatment by England ahead of the infamous 32-33 Ashes tour.

Without getting overly technical, England Captain Douglas Jardine and his bowlers developed a tactic known as ‘Bodyline’. This meant stacking the fielders on one side of the batsman, bowling in a way that would cause the ball to pitch at the upper body, rather than the stumps. The batter had two choices — awkwardly play the ball and risk being caught, or take a blow to the body. To maximise the effect of this tactic, Larwood’s pace and accuracy were essential.

Bodyline was effective — and controversial. Australian Bill Woodfull was struck by a Larwood delivery as the series reached its most febrile in the third test, Bert Oldfield had his skull fractured (no helmets in those days), and a braying crowd threatened to invade the pitch in response to what were perceived as unsporting tactics.

This sentiment was echoed by the Australian Board of Control, whose telegram to the Marylebone Cricket Club threatened to derail the entire tour. Trade between the two countries was threatened, and the allegation of unsporting behaviour was withdrawn, so the series continued.

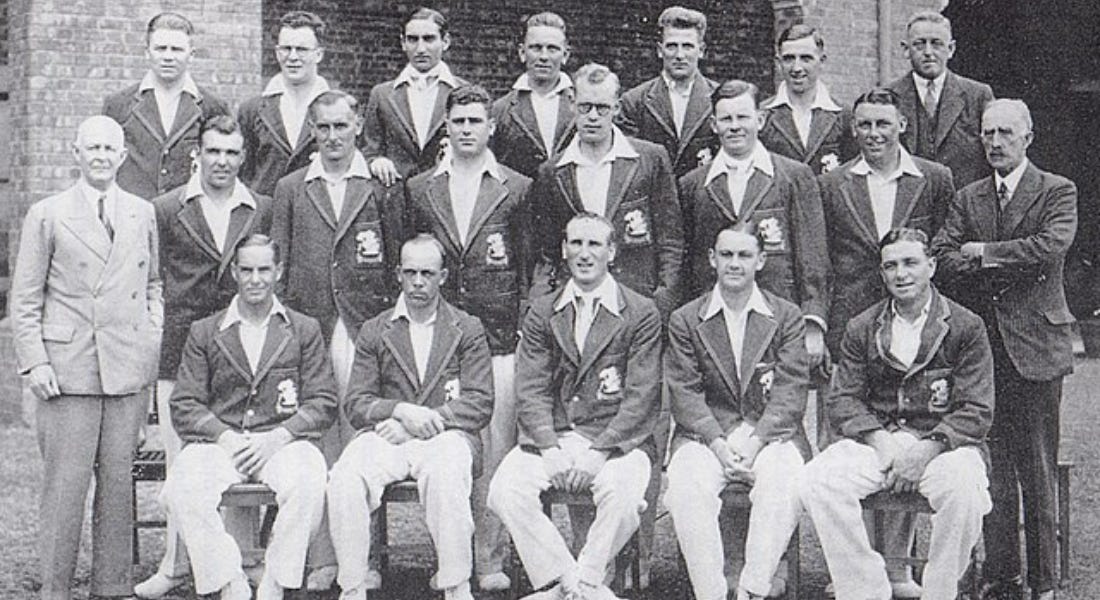

England won the series 4-1, with Bradman averaging 56.57 (measly by his own standards), and Larwood taking 33 wickets, more than any other bowler. In the modern era, Larwood would have been made an MBE on arrival back in England. But instead, he was thrown firmly under a bus.

While diplomatic tensions had eased, the cricketing establishment took the appeasement route. “They insisted Larwood should apologise to the Australians. Larwood insisted he was bowling as his captain asked, refused, and was never picked for England again,” Peter added.

He also received hate mail from Australians and Englishmen alike, questioning his motives and his tact. Peter says, “A story which Larwood relates in his book on Bodyline sums up how he was treated by the Australian press and authorities at the time. He reports that when out in Sydney, he passed a mother and her child; the child said to their mother as he went past, “he doesn’t look like a murderer!’”

Read more:

However, this was not the case in Nottingham. “Larwood was one of their own, one of the best at what he did,” Peter says. A fundraiser was held for Larwood and Bill Voce (also born in Kirkby). “In a rare show of co-operation among the press, the three Nottingham papers all supported the fund,” he adds.

In truth, an injury sustained in Australia meant that he scarcely bowled for the two seasons following the Bodyline tour. “Indeed, at one point Notts were selecting him for his batting and fielding,” Peter says. “A fit, fired-up Larwood would have enhanced any side and even at a slightly reduced pace, he was probably still worth a place in the England side. But we can never know what he might have achieved.”

Larwood retired from county cricket in 1938 and lived in relative obscurity, opening a sweet shop in Blackpool before he made his home in Australia, where he was once reviled as a blood-thirsty villain. “One of the great ironies of the game,” Peter says.

Larwood finally began to receive the domestic recognition he deserved in the 1980s. The Larwood and Voce stand was opened at Trent Bridge in 1985, and John Major — who was “not coincidentally a cricket fan” — made him an MBE in 1993. Posthumously, he was inducted into the ICC Hall of Fame in 2009.

Larwood died on July 22 1995 — able to have felt the late recognition his cricket career deserved. There are boots, caps and jumpers in storage at the ground, and, as well as the stand, the Pavilion clock is named after him — an appropriate tribute for a player and a man whose time in cricket was unfairly cut short.

Larwood and Don Bradman were fierce rivals, two very different people, with different pasts and future after their on pitch battles of the Bodyline series. And while the mutual distaste cooled with time, there was no cliché friendship that blossomed — but when Larwood died, Bradman declared that his name would live in history as one of the greatest fast bowlers of all time.

It’s fitting then that, in the heart of the mining town that produced such a player, the two men are facing off in bronze forevermore.

🤳 Keep up with us on socials on Instagram and TikTok

✉️ Send stories such as press releases and feature ideas to editor@thenottsedit.com

💰 Want to feature your business in The Notts Edit? Email Eve Smallman at editor@thenottsedit.com to receive our media pack

☕ Enjoying The Notts Edit? Buy us a coffee on Ko-Fi and help fuel our words